Manco Inca Yupanqui, king of the Inca people and general of the armies, looked down the steep terraces on Ollantaytambo at the oncoming Spanish army. “Fire!”, he said to his archers. But the Spanish kept coming. It was January 1537.

“Fire!”, again he called as the enemy came closer, this time to his spearmen and to anyone with a spare hand to throw a rock. The Spanish army reeled under the onslaught. Sensing an advantage he flagged his men in the hills; they let loose blocked canals and flooded the valley below. The Spanish cavalry was swamped, and the Spanish general called a retreat. So ended one of the few major battles the Inca won over the Spanish.

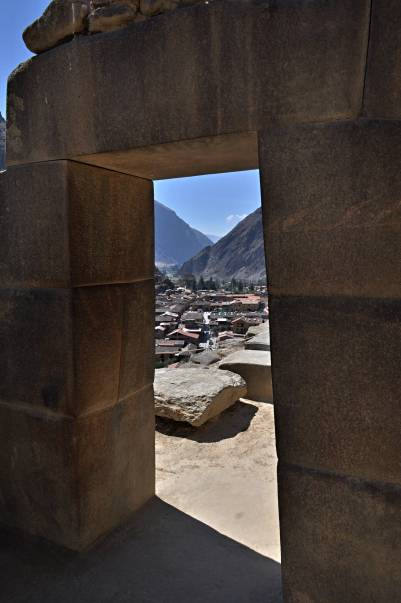

Thanks to this one event the terraces and buildings at Ollantaytambo in the Sacred Valley of Peru became known as a fortress, but for most of its existence its use was religious or for astronomy. It’s possible the battle didn’t even reach here, it was the last line of defense.

The lower and mid levels of the terraces at Temple hill are made of field stone. They’re arranged with skill, much as you might stack a cord of wood, but they do not have the dressed stone aspect of the top tiers. Our guide tells us that the terraces are likely pre-Inca, and the dressed stonework at the top came later after the Inca conquered the valley and opted to turn it into a regional administration and religious center.

This doesn’t mean the Inca only did fancy dressed stonework. That level of masonry was reserved for temples. But the bigger question is, how the heck did they do it?

No mortar was used. Individual blocks weighed from hundreds to thousands of pounds. Yet the pieces interlocked as tightly as a 3D jigsaw puzzle, without enough space between the stones big enough to fit a piece of paper. You’d think the Spanish would have asked.

Maybe they did. Maybe they decided it was too time and labor intensive to bother with. Maybe the Inca stonemasons were secretive, and would only share their techniques with apprentices who’d been sworn in, wearing funny hats and robes, and taught the secret handshake. In any case, the Spanish did not record the how.

One thing is clear, the Inca never finished their remodel. Some of the stones show clear signs of unfinished carving, and semi-completed stone blocks lay here and there.

Atop the temple is a window that, only on the solstice, June 21, lets light through to strike a pillar. This signaled a change in the growing season.

When you hear about Peruvian history, it’s always Inca this and Inca that. But the Inca empire was short lived – it only lasted from 1438-1533, less than 100 years. Huge amounts of preconquest Peru history predates the Inca. And to split hairs (skulls maybe?), the name Inca only applied to the rulers rather than the riff-raff, it’s the Spanish who started its use as a generic term. So what’s the big deal?

The Inca people showed up around the early 13th century, and were just another tribe in the Cusco area until the reign of their 9th king, Pachacuti (1438–1471). Pachacuti Inca Yupanqui made his name initially as a military commander, he defended Cusco from the Chanka while his father and brother turned tail and ran. Perhaps he took his victory as an omen, as he followed up by beginning an unprecedented expansion of empire, which was continued by his son and grandson. At its largest, the empire joined Peru, large parts of modern Ecuador, western and south central Bolivia, northwest Argentina, north and central Chile and a small part of southern Colombia into a state comparable to the historical empires of Eurasia.

Pachacuti and Sons didn’t do all of this at the point of a spear, they also used more diplomatic methods. That’s where the crop circles come in.

When I first saw pictures of the “agricultural” terraces at Moray, I was thinking the archeologists had been sniffing too much dust, it looked like an amphitheater to me. But once I was on site and saw the scale of these terraced depressions it was clear that any actor would need to have the voice of a god to project from bottom to top. You’d need a big theater troupe as well, there were three of these “amphitheaters” on site.

Then the guide started talking about how the archeologists had tested the soil, and found that some of it was imported from other parts of the empire, and seeds of various sorts had been found at the different levels. It began to look like this really was an agricultural research station.

Not convinced? Consider this. Each of the terraces was engineered. It wasn’t just dirt, it was a layer of rocks, then a layer of gravel, then a layer of sand, then a layer of dirt. Peru’s climate is rainy season and dry season, and this helped prevent flooding in the rainy season. To top that off, there were irrigation channels that could be opened and closed to control how much water got to a section of each terrace.

Still not convinced? How about this: each terrace is about 5 or 6 feet higher than the next. When you add irrigation, that amounts to as much as a 3°F difference from level to level, and as much as 27°F (15°C) difference from the bottom to the top of a pit. So, they can not only test different plants, they can test them for different climatic conditions. Using this information, the Inca became so successful at farming they could not only survive, but build up food stores.

Still not convinced? How about this: each terrace is about 5 or 6 feet higher than the next. When you add irrigation, that amounts to as much as a 3°F difference from level to level, and as much as 27°F (15°C) difference from the bottom to the top of a pit. So, they can not only test different plants, they can test them for different climatic conditions. Using this information, the Inca became so successful at farming they could not only survive, but build up food stores.

So what does all this have to do with Pachacuti and Sons?

While Pachacuti had a reputation for being brutal, he wasn’t dumb. He knew he’d have better luck with his conquests if he could do so without violence, so he’d use a rough diplomacy when he could – both the carrot and the stick. He’d send spies to the lands he was interested in and learn of their military strength, wealth, and food status.

Then he’d send ambassadors with gifts. They’d ask “how’s your corn crop doing”, knowing that the crops were suffering from lack of water. They’d say, “we have extra food we can help you out with now, and we’ve developed seeds that will grow in dry conditions. Would you like some?” They’d say “yes, thank you”, and the next year the ambassador would say, “if you want more help, if you want to be as prosperous as we are, you’ll have to join our federation.” Because that’s what the empire was, just loosely aligned tribes, paying taxes to the central Inca government and following their lead. Most would say “yes, we’ll join”, knowing full well if they didn’t the stick would be next.

But eventually the Spanish showed up, with their superior technology, and their diseases (smallpox in particular), and their aptitude for recruiting natives that had been subjugated by the Inca. Two of Pachacuti’s great grandsons had just finished a civil war over who was going to be the next king, and the Spanish used the residual animosity from that to recruit more natives for their army.

By the time the battle of Ollantaytambo occurred the Spanish were already in control. Manco Inca Yupanqui was actually a puppet king, the Spanish had put him in power. If they had treated him well he’d have probably worked for them, but they did not. He escaped and raised an army of 200,000 for a rebellion. Ollantaytambo was a victory, but Manco didn’t think he could hold it in the face of Spanish reinforcements so he retreated to the jungle village of Vilcabamba. That remnant of Inca resistance survived until 1572.

When I started my day in the Sacred Valley I knew none of this. I had no idea how the Inca empire had grown so fast and fallen so fast. The idea of the Inca having an agricultural research station seemed ridiculous – weren’t they primitives? Judging by their engineering, maybe not so much. Judging by their brutality, maybe so. But have things changed that much?

My god the photos are sick, the one with the crop circles on the banner in particular really draws you in. I like the way you captured the depth in the canyons too. I want to go. Never had much interest in South America but now a lot more so. I almost went down there to climb Aconcagua with a friend (would have been WAY over my head) but wisely decided against I think. They leave the corpses on the mountain you know.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks Bill. When I have a chance to go to an amazing place I feel almost duty bound to come up with some pics that give a feel for the place. Some folks can do it with just words, I have to work a little harder at it.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Well you made me want to go there, so nice work, it paid off.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’m convinced, I’m convinced…..you can stop now, already! I enjoyed this essay, Dave. Cool pictures, too.

LikeLiked by 1 person

You may never think of crop circles the same way again… 😉

LikeLike

Found it very interesting – thanks Dave. Maybe I’ll make it one day- by coincidence 2 work buddies were just talking about this area today!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks Lindy. I guess that’s the challenge: how to make history interesting.

LikeLike

Fascinating and that header photo is way cool and when you find out what it is, you’re hooked into Incas! I keep looking at the stonework shots and wondering how such precision was created. There are many “How on earth’s” when you look at past civilisations. Great post, Dave, thanks for sharing….

LikeLiked by 1 person

It is a mystery, isn’t it. Our guide suggested time wasn’t a big concern for people of that era, apart from when the growing seasons were. Taking on a project like that was intended to please the gods (not unlike more contemporary cathedrals), so however long it took, it took.

LikeLiked by 1 person

An agricultural research station? Goodness, they were very sophisticated farmers. Stonemasons too by the sounds of it. 😀

LikeLiked by 1 person

Not bad for 500 years ago.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Not bad at all.

LikeLiked by 1 person

You take us here Dave with your writing and incredible photos ~ wow, what a history and a feel for how impressive our ancestors were in making a great life. How I’d love to see what you’ve seen here for myself.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I suspect this is the sugar coated version of Inca history. Some of the other things I read and heard from our guide suggests brutal inhumanities, enough to scare people into kowtowing without much resistance. It was a nice place for photos though.

LikeLike

Great pics, especially the main one of crop circles.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yes, that one does seem popular, I guess the nested circles draw you in. I’m kind of partial to the Sacred valley shots myself.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I really liked Ollantaytambo. Though “like” may be the wrong word. The day I went, there was hardly anyone else around, and the feel of the place was both melancholy and disturbing.

LikeLiked by 1 person

There is something about seeing the remnants of a civilization that’s vanished that’s a bit sobering.

LikeLiked by 1 person

What a breathtaking location. The Inca certainly left their mark on the world. Great post, crammed with interesting details and wonderful images.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I was a little concerned this one would be too much boring history and not enough personal response to it, but it turned out OK. 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

Such a wonderful post. As a teenager, I fell in love with South America and read everything that was available in out town library. Your photographs give a perfect picture of the place, and I feel like being there myself 🙂 When I think of all these structures, the first thought is – they have to be very important. The second thought always is – why there is no growth on the stones? Wind and animals always spread seeds – why the stones a bare? There must be no fertile soil, even in the cracks in those stones. You theory is very interesting. What else would be more important than food for those people? My guess is that there were some clay or pottery containers placed on the stone circles and filled with soil – it was how they grew their crops 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

The stone circles themselves were filled with soil, including layers for drainage, and integrated irrigation. It does seem like there’d be more growth in the stone walls between terraces. Those were stone and some sort of mortar. I guess it’s solid enough to discourage seeds. I do wonder what the terraces look like in the wet season, we were there at the end of the dry season.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I think there were some clay containers to hold the soil. Rain would wash away the soil if it wasn’t protected. These containers wouldn’t survive until the present time.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Nicely done, Dave. I love the way you bring the history to life with your story telling.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you. I put quite a bit of work and research into that one on top of what I learned while there, I’m glad it turned out well.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I was amazed by Moray, too. Our guide didn’t go into the kind of detail yours did regarding the agronomic aspects of the circles. We just stood at the top and looked down. The Incas were great hydraulic engineers, too. I’ve seen photos of these circles during the ‘wet’ season, and they do look much more impressive, although what they actually looked like during the height of Inca power must’ve been something akin to the Hanging Gardens of Babylon. Your photos are well chosen and dramatic, as others say. Good job.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thank you Zoomeboshi. It would be fascinating to be a fly on the wall during the height of the Inca, to see how they did their farming and terraces, and especially how they did that precision stonework.

LikeLike

Thank You, Thank you…This was just Amazing…

LikeLiked by 1 person

You’re welcome, you’re welcome, it was an amazing place. 🙂

LikeLike

I, too, was captivated by the history whilst in Cusco. I’ve got to say that, like yourself, I was suprised by the relative quickness with which the empire fell, until I stop and considered how the Spaniards must’ve looked like to the Inca: bigger, burlier, bearded, covered in shiny armor, with horses, dogs of war, guns… It must’ve been like War of the Worlds for them.

Another thing that somebody told me, and I don’t know if you heard that one as well Dave, was that smallpox was already endemic in the Inca empire before the arrival of the Spaniards, having travelled down from Mexico which, at the time, was already under European control. With hindsight it shouldn’t be too surprising, but there and then it kind of was!

Fabrizio

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yes, I’d heard that smallpox had already cause serious damage to the population, and that a civil war that had just completed prior to the Spanish arrival only made things worse. I suspect the factors you pointed out might have been exaggerated even more by the Inca’s spiritual beliefs. They may have thought the ease with which their king was captured was a sign from the gods. Still, it’s surprising they weren’t more successful based purely on manpower.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Wow! Really enjoyed reading about your experience. Great information about Inca.

The images are superb, especially the crop circle. It must have been really thrilling!!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks Ratheesh. More fascinating than thrilling really, and it gave a real sense of the power and weaknesses of the civilization.

LikeLike

Interesting!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Who’d have thought it?

LikeLike